LITTLE BOXES

by Jessica Todd, May 2014

A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts

INTRODUCTION

"Jefferson’s [National Survey] presupposed that the environment actually had a strong effect on human beings. For him, it took on the quality of an active force, a formative influence over the individual and the larger society. The right surroundings were considered one of the proper conditions that allow men and women to think clearly and behave rationally; they were a necessary part of a democratic republic.” (1) (From Building the Dream: A Social History of Housing in America by Gwendolyn Wright.)

From the earliest days in the formation of our country, a plan was set in motion to quietly promote the values held by America’s political leaders by developing a “generalized idea of a model dwelling which would form a good American.” (2) We look at our country’s domestic architecture and relate to it emotionally, financially, or physically, but rarely do we approach it politically. Our surroundings act as deliberate propaganda to persuade our thoughts, actions, and reactions in our everyday lives.

My process as a visual artist always begins with observation. My work is a reflection of the world as I perceive it and therefore takes on a narrative quality. I have always been most articulate visually, and the physical process of making facilitates the examination of my initial observations as a kind of therapeutic research method. The work presented in my thesis exhibition Little Boxes is born from my experience growing up in the American suburbs. The ideas represented came to fruition through analyzing the characteristics of the American suburban environment and its residents, exploring my own psyche as a product of that environment, and compiling related research in sociology and the visual arts. Furthering this analysis simultaneously through my artwork during my time at Kent State has allowed me to focus my study and learn to visually express my viewpoint to my audience. The materials, forms, and processes I use are always in response to the concept I am working to convey. The resulting exhibition utilizes contemporary craft media in direct relation to the body to speak intimately about the impact of suburban structures on the collective American subconscious.

I spent my childhood riding my bike up and down a winding asphalt cul-de-sac, building forts in manicured bushes perched neatly atop little manmade hills, and looking out my second-floor bedroom window to a sea of pastel siding and gray rooftops set off from bright green grass. Growing up it seemed the neutral backdrop to a melodrama of childhood. But as I grew older and the subdivisions spread rapidly like an infection over the landscape around me, my environment suddenly became conspicuous. I felt a distinct emptiness in that space, a lack of authenticity, belonging, or larger cultural identity. My parents, brother, and I seemed to be a four-person single family unit floating in a sea of American dreams, a prescribed, pristine environment that promised so much yet left me with so little. By the time I left for college I was eager to go out into the world and find a connection to something real.

In my third year at Penn State University I jumped at the opportunity to study abroad in Barcelona, Spain and returned after graduating to live there for a year. I used my investigation and interpretation of Spanish society to reexamine my own upbringing in the American suburbs and gained a new level of comprehension and criticism of the world from which I came. In 2009 I moved back to Virginia, but as predicted by Thomas Wolfe, I couldn’t go home again. The place that was once so comforting and familiar felt overwhelmingly aloof. Throughout my lifetime the DC suburb of Loudoun County had transformed from a population of approximately 57,000 in 1980 (3) to over 300,000 in 2010 (4), and became the richest county in the country by 2012 (5). This kind of economic growth and population increase in a county that was primarily farmland two decades before was the perfect recipe for prototypical suburban sprawl; my childhood home, built in 1985, was among the first of many little boxes that now litter the landscape. Upon my return from Spain I saw the same homogeneity I had noticed in high school but through a new lens. It was no longer simply boring – it was parasitic, cultish, constricting, and burdensome.

I needed to learn more about my environment and how it had formed me as a person. I began my research looking into the origins of suburbia in the United States: What created the picture of suburbia we know today? The formation of our country as we know it began with Puritan settlers in seventeenth century New England. They drew heavily from English traditions but sought to develop a new society and environment that fostered their Puritan way of life. In the New World they saw the opportunity to build communities from the ground up the way they imagined God would want them to be. Their focus on creating physical manifestations of intangible beliefs and morals has continued into contemporary society, a value system constantly teetering somewhere between “self-confidence and pride” and “fear of not being able to live up to one’s ideals.” (6) Puritans believed that every person was preordained by God to exist within a certain societal status. However, they also had the free will to choose whether to obey or disobey God and were therefore constantly second-guessing themselves. They created communities that would remind them on a daily basis the way they were meant to live their lives, and that would help them to carry out the responsibility of keeping their neighbors in line as well. (7)

As time went on, the country and population began to rapidly expand. Homesteaders were moving quickly into new frontiers and building homes out of necessity with little or no consideration for uniformity. This worried America’s leaders, such as Thomas Jefferson, who viewed this transient, haphazard housing pattern as a threat to a united republic. The question arose, “How could Americans create an environment that protected the respect for order, self-sufficiency, and spirituality they held in common, without imposing on the freedom of each individual and each family to live as they pleased?” (8) The solution came in the idea of the model home. Rather than positioning this calculated construction as a governmental regulation, they advertised the model home as an inspiration to homebuilders and a solution to designing an inexpensive, easily repaired, and aesthetically pleasing domestic structure. Of the categories of model homes developed during that time, the most emphasized was the detached cottage for the independent farmer and his family. (9) Detached homes came to represent, “personal independence..., family pride and self-sufficiency..., an expression of democratic freedom of choice..., [and] the pattern of private enterprise, rather than planning of the overall public good, which characterized American society.” (10)

This basic concept has endured through to the present day. The 2000 census confirmed that the percentage of the United States’ population living in the suburbs now outnumbers that of rural and city populations combined. The modern-day suburbs continue to diversify in race, ethnicity, lifestyle, and socioeconomic profiles. America’s suburbanite is no longer solely white, middle-class, and married with children. (11) The 2010 census revealed that non-white populations in the suburb had increased seven percent over a decade, and that the suburbs of the 100 largest metropolitan areas are now one-third non-white. Twenty years ago, well over 50 percent of America’s poor metropolitan population lived in the city, but by 2000, suburban poor were starting to catch up. Among the increase of 5.4 million people living in poverty in metropolitan areas from 2000 to 2010, two-thirds live in the suburbs. (12) However, the idyllic image of suburbia persists. Andrew Blauvelt, Walker Art Center’s Design Director and Curator, writes, “Despite the real or perceived challenges of living in suburban environments, demand for such places will not diminish...The problem with so many end-of-suburbia theses is that they forget the most powerful thing about suburbia – its symbolism and the idealism associated with it. What might be surprising to critics of suburbia is not that most people choose to live there, but that they do so contentedly.” (13)

It became clear to me through my research that the concept of suburbia is a deeply-rooted American institution that transcends race, origin, class, gender, and lifestyle. I felt a strong pull to create work that addresses our attraction to suburbia and the underlying consequences of buying into it. Drawing from earlier works I completed at Kent State and ongoing note-taking and sketches, I developed a visual language to express these concerns through my thesis exhibition, Little Boxes.

EIGHT EXTERIOR COLOR CHOICES FOR THE COUNTRYSIDE SUBDIVISION

My first response to this research is the piece Eight Exterior Color Choices for the CountrySide Subdivision, a set of eight dyed and sewn dresses that address the way uniformity in housing is used to enforce uniformity in society (Figure 1). The planned community where my childhood home is located, CountrySide, has a “Community Guidelines Handbook”, a 140-page document that addresses the exterior appearance of every house in its jurisdiction, standardizing everything from paint colors to fences to gutters to mailboxes. On the subject of siding they write, “When making color selection, please refer to McCormick’s “Colonial Exterior Colours”, which are the original exterior colors used in most of CountrySide. Any variation from the McCormick colors will be reviewed on a case-by-case basis.” (14) The subject of “Color Changes” continues for nearly two pages. (15) By transposing the regulations on exterior paint colors from the houses we live in to the clothes we wear, I seek to affix this extreme conformity to the body and, in turn, the human psyche.

To make this piece I dyed eight pieces of cotton fabric using Rit Dyes to match the eight authorized McCormick Colonial Exterior Colors (16) and created a basic dress pattern that represents a standard uniform. Though the dresses are clearly feminine garments, the focus is not necessarily on the quintessential housewife. Women are more likely to be associated with the home, whether or not they consider themselves as housewives, and my choice to create a female garment rather than a male garment exploits this subconscious association. (Of the next two thesis works discussed below, Suburban Growth Series includes a male figure and the series of lockets are not gender-specific. This intentional inclusion of men indicates that both genders are affected by suburbia, though the focus on women in this piece follows that women may be impacted more.) The dresses are displayed on hangers to implicate their wearability. The white trim on the neckline further homogenizes the dresses and references the mandatory white trim indicated in the aforementioned handbook. Each color’s designated reference number and name is typed out, printed onto fabric, and attached to the bottom of the dress using a fusible interfacing. The font and form mimic the labeling of paint chips while referencing practices historically used to dehumanize the wearer (Figure 2).

Standard uniforms and numbers in the place of names are techniques used by prisons, cults, and, notoriously, the Nazis at the Auschwitz concentration camps. (17) Doing so leads to “a weakening of self-identity.” (18) One study shows, “As they [begin] to lose initiative and emotional responsivity, while acting ever more compliantly, indeed, the prisoners became deindividuated not only to the guards...but also to themselves.” (19) Even outside of prisons, this practice is very much present in contemporary society. Many people regard this custom with suspicion and horror. For example, conservative pastel dresses and braided hairstyles worn by female members of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (FLDS), the infamous polygamist cult run by Warren Jeffs, are a frightening visual indication of the power the organization’s leaders hold over its disciples. (20) By referencing this recognizable practice of manipulation, I push the viewer to equate home standardization, which is blindly accepted, with a more menacing version of standardization to reveal its underlying intent.

Artist Cindy Sherman’s Film Stills feature Sherman disguising herself as vaguely recognizable female characters. In doing so, she places herself inside of the suppressive collective identity of the female figure in popular culture. By taking on these roles herself, she removes her individual identity and calls attention to our assumptions about what we see and deduce from the image alone. (21) The implied wearer of the Eight Exterior Color Choices dresses similarly absorbs her personal identity into the collective identity of suburbia. In this way, I expose our subsequent assumptions about the wearer, knowing only the type of house in which she lives and the way suburban women have been represented in popular culture.

The bland color palette presented in the eight dresses pokes fun at the guise of individualization in suburban America. Residents are presented with what appears to be a choice of colors to represent their own individual styles and preferences; however, they can only choose from a grouping of preselected colors that already fit into the mold created by the developer. This is even more harmful than offering no choice at all, as it creates a deception: The residents feel as though they have participated in a democratic choice when in reality they have exercised almost no choice at all. Content in their contribution of personal expression, they never desire to push the boundary further.

Artist Sean Morrissey uses printmaking techniques to discuss the loss of individuality that occurs in the suburbs. In his series Swatches, (22) extracting repetitive forms and creating simplified silhouettes causes the individual structures to meld into singular forms where one cannot be discerned from the next. Similarly referencing paint chips, he titles his works as such to emphasize these structures as ornamental representations of an ideal of homeownership rather than practical modern dwellings. Their ubiquitous presence on the American landscape makes them seem to be the only suitable option. (23) The concept of suburbia is so pervasive that the desire to participate in it outweighs its obvious negative side effects on self-identity, architectural diversity, and the environment.

SUBURBAN GROWTH SERIES

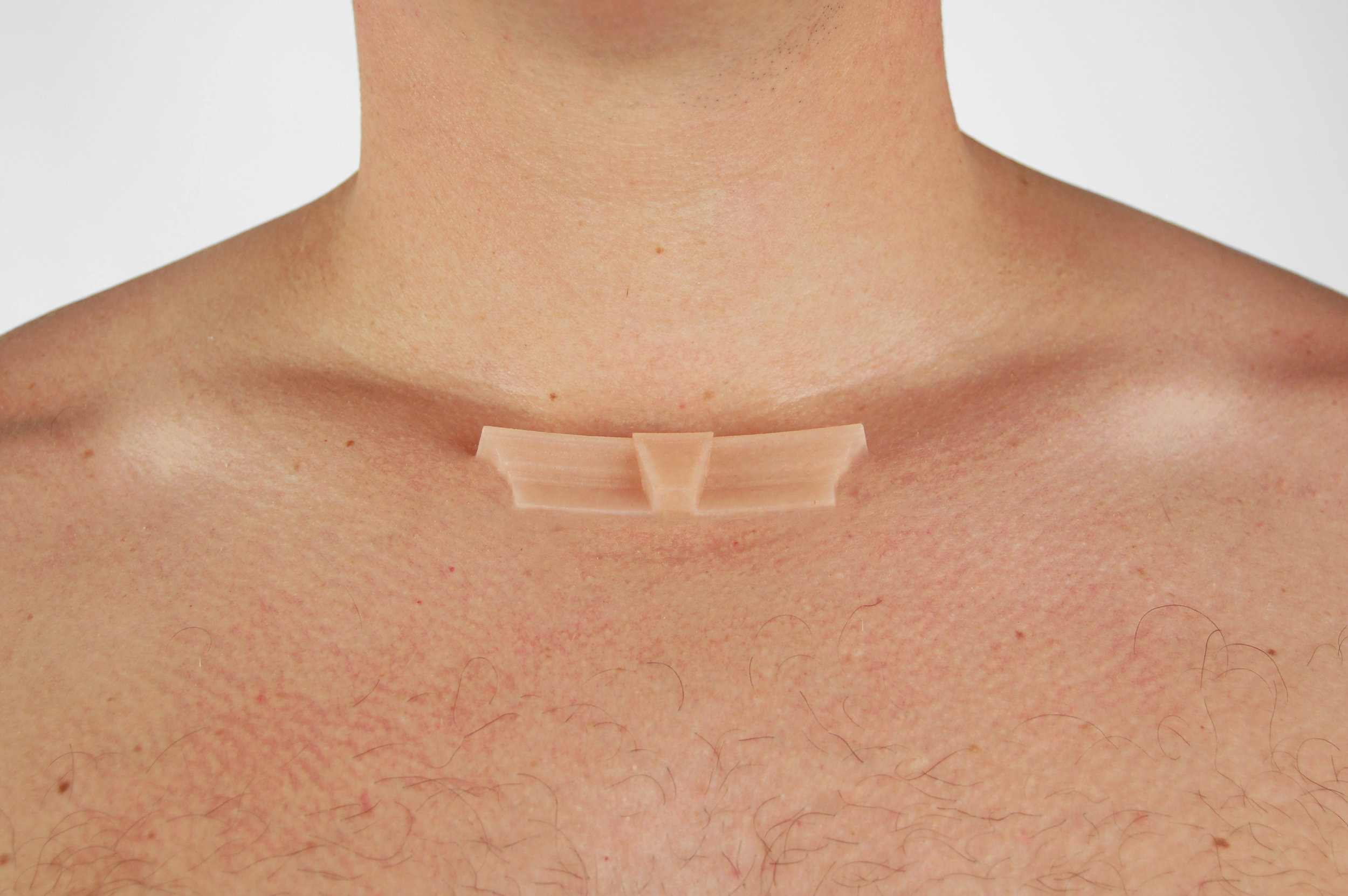

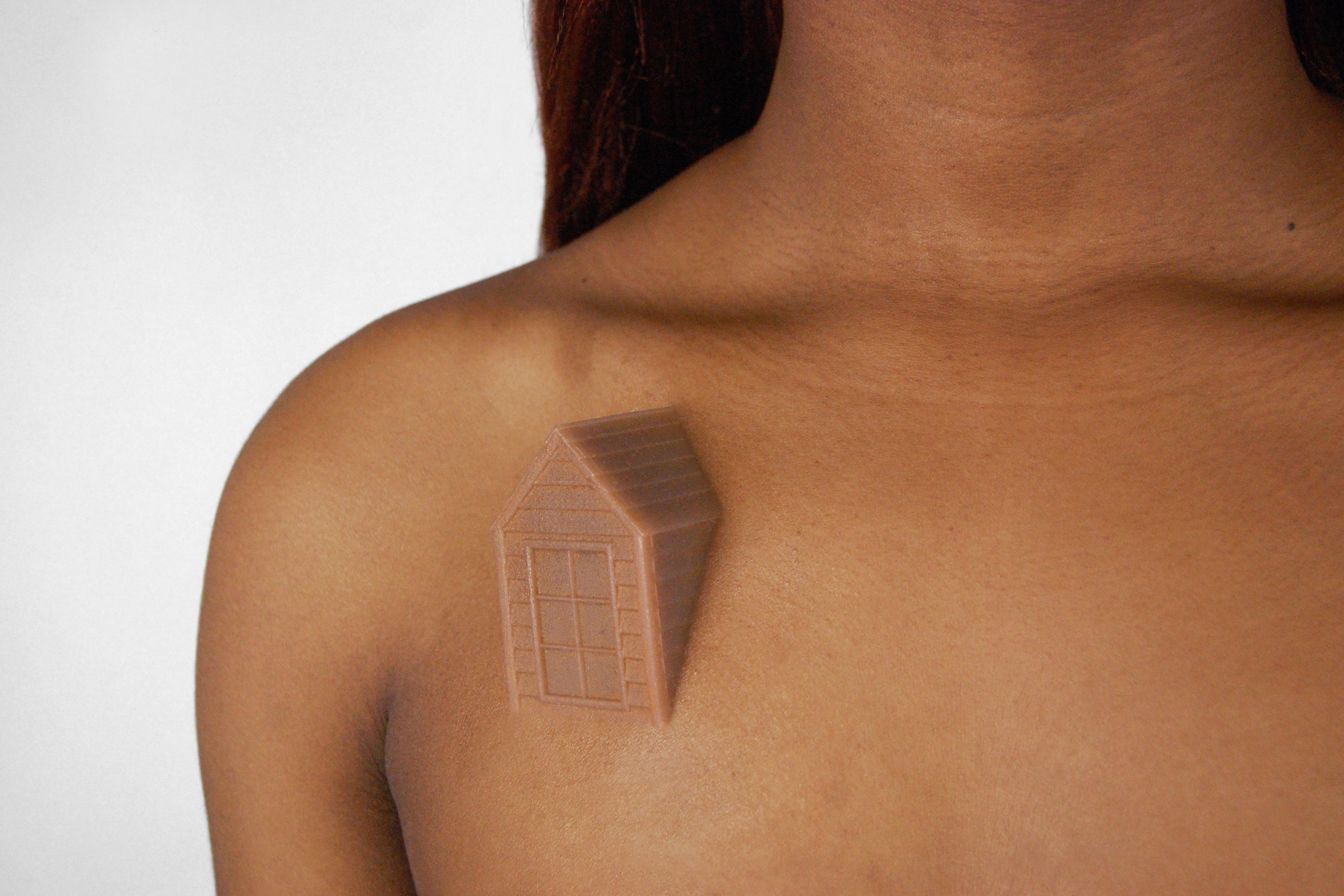

With my next piece I wanted to further explore the idea of the indoctrination of “American values” via familiar suburban structures. In the photographs of the Suburban Growth Series the propaganda of suburbia has been so accepted and absorbed that it manifests itself from the inside out (Figures 3-7). Rather than wearing the piece on the body, I made the work appear to be part of the body, emerging and growing out of the skin itself. Body and architecture fuse as one to illustrate that no human being exists as an autonomous entity; we are constantly informed and influenced by our environment, relationships, and experiences.

Using Rhinoceros, a 3D-modeling program, I designed and digitally constructed familiar suburban façade structures to human scale. The digital models were sent to a 3D-printing company, Shapeways, where they were printed using Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) with a nylon powder. I then coated the printed models with a protective finish and created molds for them using a two-part tin-cured silicone rubber, Mold Max 15, made by Smooth On. From these molds I cast the models in Dragon Skin FX-Pro, a platinum silicone rubber used to create makeup appliances and skin effects most frequently in theater and film. The Dragon Skin was dyed with Silc Pig Silicone Pigments to match each of the models’ skin as closely as possible. The Dragon Skin appliances were then attached to their respective models using Skin Tite, a skin-safe silicone adhesive, and photographed on the body. (24) I later manipulated the photographs in Adobe Photoshop to blend the appliances into the skin and add texture to their surface.

Lauren Kalman is an artist working in contemporary craft, video, photography, and performance whose work focuses on the body and skin. In her body of work Blooms, Efflorescence, and Other Dermatological Embellishments, (25) set stones are attached to acupuncture needles and are stuck directly into the skin in formations that mimic various dermatological conditions. (26) She writes, “Skin is the body’s interface with the world...It serves as protection for the body and as a signifier of the internal conditions of the body.” (27) For example, a rash appears on the surface of the skin as a visible indication of the body’s allergic reaction to something. In much the same way, the Suburban Growth Series uses these externally visible structures to reveal the psychological effects of suburbia on the wearer.

Suburban Growth Series exists only as photos where the structures appear to be growing beneath or implanted under the surface of the skin; the silicone appliances are not presented in the exhibition and the material and process are not revealed (Figure 8). Using a white backdrop and excluding facial expression or body language from the photos, the piece is left ambiguous as to whether the structure is an unwanted tumor-like growth or an intentional form of personal expression. The structure may be interpreted as a subdermal implant chosen by the wearer as a kind of badge signifying his or her cultural identity. Ancient practices of body modification by indigenous cultures gained popularity in the United States and Europe in the early 1990s, beginning with a mainstream acceptance of tattooing. More extreme versions of modification began to emerge as other practices from indigenous cultures were appropriated and adapted. Scarification practices originating in Africa developed into the practice of subdermal implants, in which metal, plastic, or other material is inserted under the surface of the skin to create a three-dimensional image. (28) Though still considered an unusual or radical procedure, subdermal implants are becoming more familiar to the general public.

The Suburban Growth Series presents the viewer with images of what may be either disfigurement or an unconventional practice of body modification, yet the image is not threatening or repulsive. This is because the appendage is clean, familiar, and conforming to mainstream culture. In Tim Burton’s 1990 film Edward Scissorhands, the strange, pale boy with a menacing collection of sharp scissors in the place of fingers is embraced in the cookie-cutter suburban town when he uses his abnormal hands to style women’s hair and practice the art of topiary. (29) Only while participating in the preservation of the norm are his differences tolerated, much the way we can tolerate the image of architecture emerging from human skin so long as it looks like something we know and trust.

Lorna Simpson is an artist who frequently works with issues of race and gender. Several of her works address the cultural significance of hair, such as her piece Stereo Styles, which features ten photos of young black women photographed from behind with different hairstyles. While these styles represent the mood or personality of the individual (as indicated by the accompanying text), they are pulled from a common visual language indicative of race, class, and cultural identity. (30) Suburban Growth Series features structures that a suburban home owner might relate to as personal expression or preference, but that carry a greater message of status and values in the larger society.

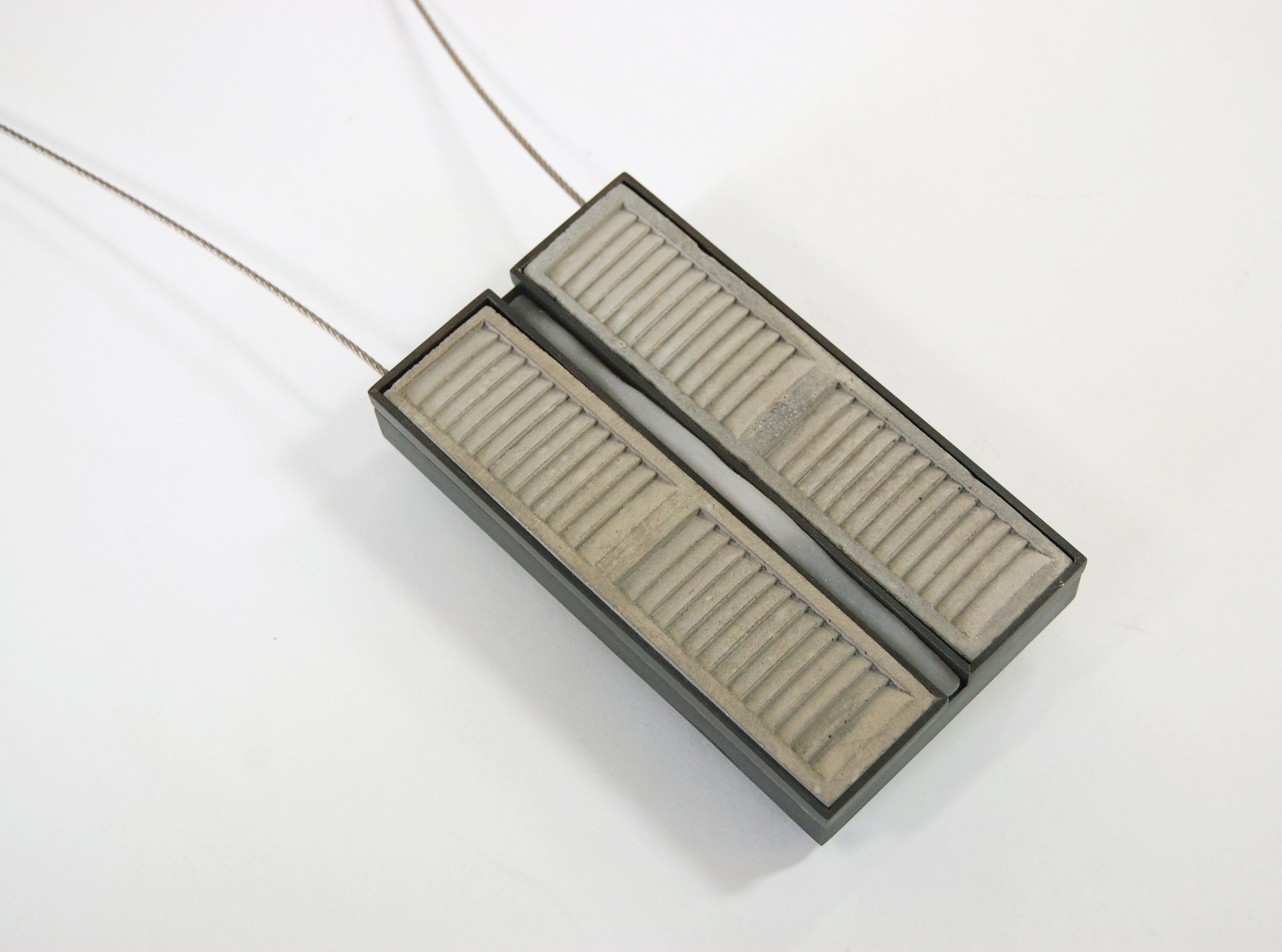

LITTLE BOXES: SEVEN LOCKETS

At this point in my work I wanted to more directly address the constricting and burdensome nature of suburbia – the pressure to kowtow and conform and the weight this carries in everyday life. In order to do this, I created physical objects that are, once again, meant to be worn (Figures 9-15). The lockets I created vary in size and weight but are all meant to have a physical presence on the wearer. In form they reference reliquaries – typically ornate containers that hold supposed remains of religious figures or holy objects. Such inconspicuous objects are elevated by their containers, signifying something precious and even talismanic. The form of the reliquary would often mimic the identity of the object held inside; for example, an arm signifying the bone of a saint or a cross signifying wood from the True Cross. (31) My lockets use familiar suburban architectural elements to indicate their relationship to the suburban home. Inside, I allude to body part reliquaries by referencing flesh. This “flesh” represents the way we suppress our natural impulses in order to fit into the suburban mold, and the way that mold imposes upon us. The focus is shifted from the preciousness of the object contained inside to the restrictive nature of the container itself, subverting the traditional function of the reliquary.

Recognizable suburban portals of outside to inside are recreated in metal and concrete to add physical and visual weight to exterior architectural elements typically produced in cheap pastel plastics. Each locket is a hollow form fabricated from a bronze alloy called “nugold.” To create the façade forms, I made silicone molds from found objects and 3D-designed and –printed models. From those molds I was able to cast the concrete pieces directly, along with waxes that I then cast in bronze using the lost-wax process. (In lost-wax casting, a one-time mold is created from silica investment around the wax model. The wax is then burned out in a kiln and molten metal is poured into the resulting cavity.) Other ornamental components required further fabrication, along with fold-forming copper for the curtain on Cedarhurst (Figure 10) and vinyl cutting a resist and sand-blasting the glass element in Springwood (Figure 13). Inside the lockets, pigmented Dragon Skin was cast in silicone molds of clay models sculpted to mimic squeezed, folded and over-flowing flesh. Threaded tubing and machine screws are used to close the lockets in a semi-permanent way rather than using an easily-opened hinge, reinforcing the idea of constriction, imprisonment, and control. Steel cable acts as the “chain”, continuing the use of industrial materials and adding to the austerity of the exteriors of the lockets. Each of the lockets are titled after street names in my hometown and are recognizable as examples of invented word combinations often used to name new suburban areas – Countryside, Cedarhurst, Lipscomb, Foxstone, Springwood, Middlecreek, and Newland.

Just as the lockets reference reliquaries, the work of artist and designer Jessica Smith, owner of Domestic Element, also uses suburban imagery in forms of traditional ornamentation. Working primarily in fibers, she appropriates traditional decorative fabric designs and creates patterns from recognizable suburban scenes. They are simultaneously ornamental and beautiful, and ominous and troubling. Toiles and paisleys transform from appealing decoration to a clever reminder of uniformity, excess, and destruction of nature. However, their intent is left entirely ambiguous: To one person they may be disturbing and subversive, but to another they may be celebratory and charming. (32)

The lockets also toy with our desire to peek inside – the gap in a curtain, a slit in the blinds – to see real life breathing inside the aloof, homogeneous structures we call home. Stephanie Liner is an artist who draws from furniture and textile design to address the connection between the human body and architecture. Her upholstered orbs include openings to view a live model seated inside, playing off of the idea of voyeurism and the peep show. (33) In her own words, “Each sculpture’s social and architectural façade houses, or entraps, a human character who becomes the personification of the psyche melded with the physical structure. This interior characters’ behavior is dictated by the façade, which becomes a manifestation of social expectations or constraints.” (34) The confined flesh inside of my lockets parallels this very idea.

When discussing the pressure to conform, we often turn to a mid-century or retro depiction of American society – the symbol of the 50s housewife, for example. However, this same pressure occurs today on online social media via the phenomenon of “image crafting.” Image crafting is “the act of carefully and deliberately constructing one’s social media content to control the way others view their life.” (35) This online portal into our personal lives acts as a globally accessible, digitalized version of the “gap in the curtain.” In the case of social media, however, we have a lot more control over what others can see. Our online profile becomes our idealized façade, and the cracks in that façade can be seen when we lose control over what is available for others to see, either due to our own loss of control over what we share or our inability to control what other people choose to share about us. Seeing those private moments – that peek inside the window – is what we most enjoy and consume in social media. Maintaining the perfect façade has not only changed form in recent years, but the public profile is more prevalent and accessible than ever before. Protecting it from infiltration has become an increasingly challenging task, and evermore precarious as unauthorized viewers, law enforcement, and the media are positioned to exploit access to it.

CONCLUSION

Eight Exterior Color Choices for the CountrySide Subdivision, the Suburban Growth Series, and the seven lockets were displayed together in my thesis exhibition, Little Boxes, as three equal components in my discussion of suburbia as a pre-meditated social structure capable of controlling our minds and bodies (Figures 16-18). The works were displayed in a small, rectangular gallery. I chose to display all of the works on the wall rather than using pedestals, for example, to encourage their consideration as art objects and provide them with equal visual weight to reiterate their equal contribution to the overarching concept. Light gray rectangles were painted on the walls behind the lockets to ground them and give them more mass in order to balance them against the physically larger and more substantial dresses and photographs (Figures 19-20). The title of my thesis exhibition, Little Boxes, plays off of the small, box-like forms of my lockets; the idiomatic uses of the word “box” in our society (“boxed in”, “thinking inside the box”); and, of course, the hit song, Little Boxes, written by Malvina Reynolds and made famous by Pete Seeger in 1963. The lyrics of this well-known song, which has been covered by countless artists and was recently revived as the theme song in the popular HBO series, Weeds, go along to an upbeat tempo: (36)

Little boxes on the hillside,

Little boxes made of ticky tacky,

Little boxes on the hillside,

Little boxes all the same.

There's a green one and a pink one

And a blue one and a yellow one,

And they're all made out of ticky tacky

And they all look just the same. (37)

Over the years of my young adulthood and through my time at Kent State, I have come from a place of strong criticism and total rejection of suburbia to understanding and owning it as a part of my personal history. I have learned that I am able to be aware and critical of my environment while still being a part of it and, in doing so, can speak more intimately about it as an artist. Wearing one of these pieces on the body out into the world involves accepting it as a part of yourself, taking responsibility for its implications, and sometimes feeling as though you’re parading the parts of it that make you feel insecure. I have found that there is freedom from those constraints in recognizing, analyzing, and understanding what they look like and how they function. This work serves not only as a criticism or warning, but as a cathartic release of the very pressures and restrictions it addresses. My hope is that through this work, my audience and I can better understand our environment, how it has formed us, and how we can free ourselves from its presumptions.

REFERENCES

(12) Berube, Alan. “The State of Metropolitan America: Suburbs and the 2010 Census.” Brookings. Published July 14, 2011. http://www.brookings.edu/research/speeches/2011/07/14-census-suburbs-berube.

(11, 13) Blauvelt, Andrew. “Preface: Worlds Away and the World Next Door.” In Worlds Away: New Suburban Landscapes, edited by Andrew Blauvelt, 10-16. New York: D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers, 2008.

(31) Boehm, Barbara Drake. “Relics and Reliquaries in Medieval Christianity.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000. Accessed April 16, 2014, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/relc/hd_relc.htm.

(20) CNN Library. “Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints Fast Facts.” CNN.com. Last modified October 31, 2013. http://www.cnn.com/2013/10/31/us/fundamentalist-church-of-jesus-christ-of-latter-day-saints-fast-facts/.

(14, 15) CountrySide Proprietary. “Community Guidelines Handbook.” Homeowner Association (HOA) Documents. Accessed April 16, 2014. http://www.countryside-va.com/docs/2014_Guidelines_20140329.pdf.

(29) Edward Scissorhands. Directed by Tim Burton. DVD. Century City, CA: Twentieth Century Fox, 1990.

(18, 19) Haney, Craig, Curtis Banks, and Phillip Zimbardo. “A Study of Prisoners and Guards in a Simulated Prison.” Naval Research Reviews 9 (1973). http://www.zimbardo.com/downloads/1973%20A%20Study%20of%20Prisoners%20and%20Guards,%20Naval%20Research%20Reviews.pdf.

(26, 27) Kalman, Lauren. “About: Statement.” Lauren Kalman. Accessed April 16, 2014. http://laurenkalman.com/art/About.html.

(25) ---. 2009. Blooms, Efflorescence, and Other Dermatological Embellishments. Lauren Kalman. Accessed April 16, 2014. http://laurenkalman.com/art/Blooms,_Efflorescences,_and_Other_Dermatological_Embellishments.html.

(5) Levy, Francesca. “America's 25 Richest Counties.” Forbes.com. Published March 4, 2010. http://www.forbes.com/2010/03/04/america-richest-counties-lifestyle-real-estate-wealthy-suburbs.html.

(33, 34) Liner, Stephanie. “Statement.” Stephanie Liner. Accessed April 16, 2014. http://stephanieliner.com/statement.php.

(16) McCormick Paints. “Colonial Colors.” Accessed April 16, 2014. http://www.mccormickpaints.com/Commitment_to_Color/McCormick_Color_Cards/Exterior_Color_Collection/.

(30) McLaughlin, Bonita. “Women Under Scrutiny.” Chicago Reader 22, no. 13 (1993). Accessed April 16, 2014. http://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/women-under-scrutiny/Content?oid=881169.

(23) Morrissey, Sean. “Basic Space.” Master’s thesis, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 2011. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1019&context=artstudents.

(22) ---. 2011. Swatches. Sean P. Morrissey. Accessed April 16, 2014. http://seanpmorrissey.com/section/214015_Swatches.html.

(28) Pitts, Victoria. In The Flesh: The Cultural Politics Of Body Modification. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

(37) Reynolds, Malvina. “Little Boxes.” Performed by Pete Seeger. Broadside Ballads, Vol. 2, Folkways: 1964. http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B000S3HIWW/ref=dm_ws_tlw_trk1.

(32) Smith, Jessica. 2011. “Domestic Element: Bio.” Domestic Element: Work by Jessica Smith. Accessed April 16, 2014. http://www.domesticelement.com/bio/.

(24) Smooth-On.com. Accessed April 16, 2014, http://www.smooth-on.com/.

(17) United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “Tattoos and Numbers: The System of Identifying Prisoners at Auschwitz.” Holocaust Encyclopedia. Accessed April 16, 2014. http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10007056.

(3) U.S. Census Bureau. “Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990.” Compiled and edited by Richard L. Forstall. Published March 27, 1995. http://www.census.gov/population/cencounts/va190090.txt.

(4) U.S. Census Bureau. “Population, 2010.” Loudoun County, Virginia, People QuickFacts. Last modified March 27, 2014. http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/51/51107.html.

(35) Whole 9 (blog). “The Dangers of Image Crafting,” March 3, 2014. Accessed April 13, 2014, http://whole9life.com/2014/03/dangers-image-crafting/ (site discontinued).

(36) Wikipedia. “Little Boxes.” Last modified March 23, 2014, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Little_Boxes.

(21) Williamson, Judith. “Images of ‘Woman’: The Photography of Cindy Sherman.” In Feminism-Art-Theory: An Anthology 1968-2000, edited by Hilary Robinson, 453-9. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 2001.

(1, 2, 6-10) Wright, Gwendolyn. Building the Dream: A Social History of Housing in America. New York: Pantheon Books, 1981.

Available online through OhioLINK Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Center